The Price of Personality: Why We Keep Buying Into ‘It-Girl’ Brands

Written by Kayleigh Carlos

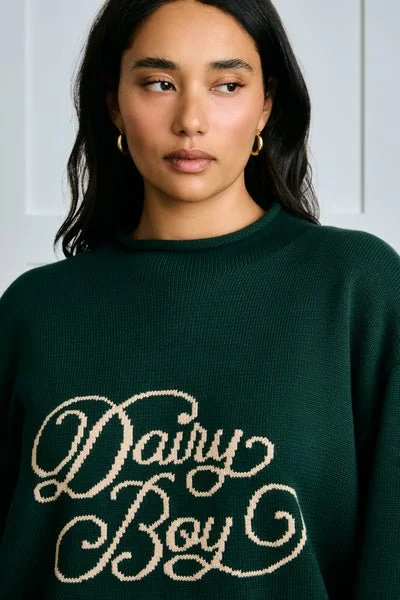

A $150 sweatshirt with a girl’s name across it. Sold out in hours. On TikTok, opinions are split: “why would anyone buy that?” versus “because it’s Parke.” Recently, fashion has entered an era where exclusivity matters more than the product itself. The rise of “It-Girl” fashion labels like Parke, Dairy Boy, and The Bar shows how buying a sweatshirt is no longer just about style. It is about showcasing how exclusive your wardrobe can be and, more importantly, who you identify with.

Parke, founded by Chelsea Parke in 2022, started with upcycled vintage denim before expanding into full collections of everyday basics and their now-signature mockneck sweatshirts. Because of limited inventory, drops often sell out within minutes, fueling the sense of exclusivity that defines the brand. For brands like these, scarcity is not just a marketing tool — it is a business model.

The appeal of exclusivity lies in how it taps into a sense of belonging and individuality at the same time. When something is limited, owning it feels like proof of being “in the know.” For teen and college-aged shoppers especially, these brands become a subtle form of social currency because it is something that signals both taste and access.

Traditional luxury fashion built exclusivity through price and prestige, but these “It-Girl” labels build it through relatability and scarcity. Instead of glossy campaigns and runways, their power comes from authenticity and digital connection which is a different kind of status symbol for a different generation. They are easily styled because of how simple they are and give customers a sense of shared identity.

Parker recently landed an in-store collaboration with Anthropologie, a move that could risk its “for the girls who know” reputation, but Chelsea has kept that exclusivity alive through recent pop-up city events where shoppers can buy custom-designed mocknecks available only in select locations.

Similarly, Dairy Boy, founded by influencer Paige Lorenze, and The Bar, founded by Bridget Bahl, have built their brands around a specific kind of cool-girl energy. Dairy Boy’s camo sweatshirts are paired with the cozy, country aesthetic Lorenze shares online, while The Bar’s varsity hoodies fit Bahl’s New York chic persona. In both cases, the product is secondary to the woman behind it. Their personal style, routines, and social media presence are the real marketing.

For many teen girls, these brands feel personal because they already follow the founders, often following the making of the brand and the pieces hung in their wardrobes. Buying a sweatshirt does not just mean owning a piece of clothing. It means buying into a lifestyle they have been watching unfold online for years. There is a level of relatability and connection that makes the purchase feel like supporting a friend rather than a faceless brand. It is consumerism fueled by familiarity and parasocial intimacy.

But the “It-Girl” economy has a darker side. The more these brands grow, the harder it becomes to maintain that sense of exclusivity and authenticity that made them appealing in the first place. When a once-niche sweatshirt appears in a major retailer, fans question whether the brand has lost its original charm. Critics also argue that these labels sell aspiration more than innovation. A sweatshirt is not worth $150 because of its quality, but because of the story stitched into it.

In the end, that is what the “It-Girl” fashion wave represents: a new kind of consumer psychology where identity, lifestyle, and marketing blur together. The question is not really whether the sweatshirt is worth the price. It is whether we are buying the clothing, or supporting the girl who made it.

Edited by Claudia Rothberg, Ava Palmieri, & Isabella Zapata